High-profile suicide served as a wake-up call in a country where forests and wildlife had been decimated

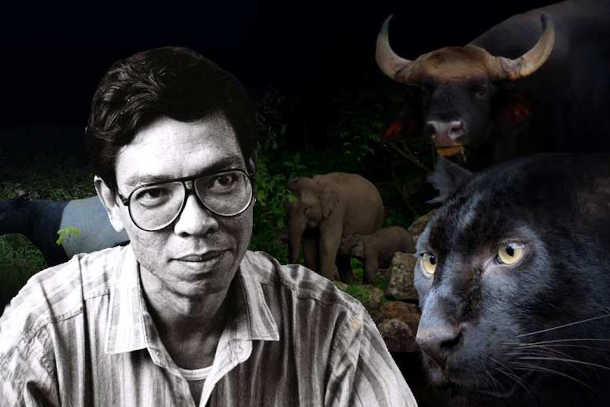

Seub Nakhasathien blazed a trail in Thai wildlife conservation. (Photo courtesy of Seub Nakhasathien Foundation)

At dawn on Sept. 1 in 1990, a single gunshot rang out in the Thungyai Naresuan-Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Uthai Thani province in western Thailand.

The shot wasn’t fired by a poacher or a hunter. It was fired by Seub Nakhasathien, a Thai conservationist and environmental activist. His target wasn’t a wild animal. It was himself.

“I decided to take my own life,” Seub, who was 45 at the time and had been working as superintendent of the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand’s Western Forest Complex, wrote in his suicide note. “No one else was responsible for this decision.”

Seub, who in photographs comes across a thoughtful, amiable man with thick grandpa glasses, wanted his death by his own hand to serve as a wake-up call to Thais in a country where forests and wildlife had been decimated.

In that he succeeded. His high-profile suicide, the Bangkok Post newspaper noted, “helped transform the status of Thungyai Naresuan and the adjacent Huay Kha Kaeng Western Forest Complex into a sacrosanct site and inspired many youth to become forest patrol staff.”

Before his final act, Seub, who obtained a master’s degree in conservation from University College London in the United Kingdom, became increasingly despondent.

Thailand’s once thick jungles had been thinned by loggers and its once abundant iconic animals like tigers and elephants had been poached into near-extinction. Yet local officials, he found, routinely ignored illegal logging and poaching, thereby creating a climate of impunity. Poachers and loggers could even kill forestry officials and get away with it.

The only way to save the wildlife sanctuary from further harm was to make it into a UNESCO World Heritage Site because the status would confer extra protection onto it, Seub reasoned. So before his death he meticulously arranged documents that contained his plans for local forests, details of how to protect them, and a completed application to UNESCO for World Heritage status of forests.

Three decades on, his call for action to save local forests and their wildlife still reverberates in the country’s environmentalist circles where the late activist is seen as a guiding light of conservationism.

An inspiration for young people

For two days on a recent weekend, hundreds of environmentalists, conservationists and nature lovers gathered for a memorial conference organized in honor of Seub at a cultural center in Bangkok. They listened to lectures on wildlife conservation. They exchanged views on environmental topics. And they watched videos of Seub and wildlife in his beloved forests.

“By killing himself Seub tried to make an impact. Make a noise, so to speak,” says Dr. Teerapat Prayoonsitti, a senior official at the Wild Fauna and Flora Protection Division of Thailand’s Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation who knew the late conservationist well.

“It’s undeniable that his final act caused people to start thinking more about the need to protect forests. But we shouldn’t dwell on his suicide. We should focus on his achievements. It’s because of those that he can serve as an inspiration for young people.”

Seub’s beloved forests in the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which was recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO the year after his death thanks in no small part to him, are doing much better than in his lifetime.

Surrounded by a 5km-wide buffer zone to separate them from villages, the area’s forests remain home to tigers, elephants, Malayan sun bears, gibbons, tapirs, wild buffaloes and several other endangered species.

Teams of rangers, who fan out across the protected area on regular patrols, guard the jungles against interlopers. Villagers help conservation work by warning authorities about suspicious activities. They have also switched to farming organically so as to avoid harming the local ecosystem with harmful chemicals like fertilizers and pesticides.

“Poaching and logging were rampant in Seub’s day, but that’s no longer the case,” Teerapat says. “Villagers play an important part in protecting forests.”

The area’s comprehensive wildlife protection measures are now being replicated around Thailand.

“We can use these forests as a model for other protected areas around Thailand,” Teerapat explains. “I’m sure Seub would be happy to know he didn’t die in vain.”

Help us keep UCA News independent

The Church in Asia needs objective and independent journalism to speak the truth about the Church and the state.

With a network of professionally qualified journalists and editors across Asia, UCA News is just about meeting that need. But professionalism does not come cheap. We depend on you, our readers, to help maintain our independence and seek that truth.

A small donation of US$2 a month would make a big difference in our quest to achieve our goal.

Share your comments